In the current discussion about digitalisation, there is one term that seems to be omnipresent and dominating a lot of media reporting (see Fig. 01). According to the newspaper FAZ, it's something "managers can talk endlessly about", [see Meck/Weiguny 2015]. We're talking about "disruption" – the economics word of the year in 2015. Of course, wherever there are advocates, there are also critics. The FAZ chose disruption as its "worst business word of the year 2015".

Digital, more digital, disruptive

The protagonists: In the shape of companies such as Uber, AirBnB, Netflix and ZipCars, competitors are emerging that are clearly changing and breaking the rules of entire industries, and moving them towards "platform capitalism". In the current debate about the brave new digital world, people often refer to these companies as outstanding examples of disruptive innovations and business models. Anyone who doesn't keep up will soon be out of the picture. At least that's how the advocates see it, and what digital companies and associations are predicting. At times, the digital age resembles a gold rush, with billions in sales racked up overnight and huge increases in the value of a succession of start-up firms. Following the Silicon Valley ideology, they are all aiming to be the next "unicorn” – the name given to a company with the potential to be worth a billion dollars.

For financial service providers, disruptive innovations are often referred to as being like the sword of Damocles. Names like Seedmatch, Paypal, Moneymeets, Ikano, Wikifolio, Ikano, MBank, Zenefits, fairr.de, Knip, getSafe, Clark and feelix often come up in the discussion. With their disruptive potential, they are said to be on the verge of knocking established banks and insurers off their perch, according to the protagonists of the digital world. The prophecies of doom range from "Uberisation of the banking sector" to "the end of classic non-digital business models".

But is this transformation in the competitive landscape towards a platform and a totally new kind of sharing economy really "disruption"? And what do decision-makers need to know about the issue? It's time to pause for a moment and take stock. Because not everything that says disruption on it actually has disruption inside – you need to take a much closer look.

Theory – Destruction and reconstruction

The macroeconomic theory of disruptive innovation can be partially traced back to the "creative destruction" thesis propounded by Schumpeter [see Schumpeter 2005]. Here, innovation is the basis for economic progress and is a process in which old structures are overtaken by new forms of organisation. Talking of the word new: The economics magazine "brand eins" defines disruption in its literal sense and concludes that: "It means the destruction of traditional business models and value chains. For the founding generation, the word is more than a macroeconomic term, it represents their attitude to life." [Ramge 2015] Over time, an economic model has clearly been turned into a fashion and lifestyle product.

Blogger and author Sascha Lobo sees disruption as "a kind of magic word" in this new environment. "It means destroying markets in their current form. So that they can be rebuilt – different, newer, cheaper", according to Lobo [see Lobo 2014]. However, the fundamental aim of disruption is not deliberate destruction. Destruction of existing business models is merely collateral damage, a side-effect.

Fig. 01: "Disruptive innovation" in the media [Source: EY 2016, p. 10]

Concept – Profitable market segments inevitably lead to a dilemma

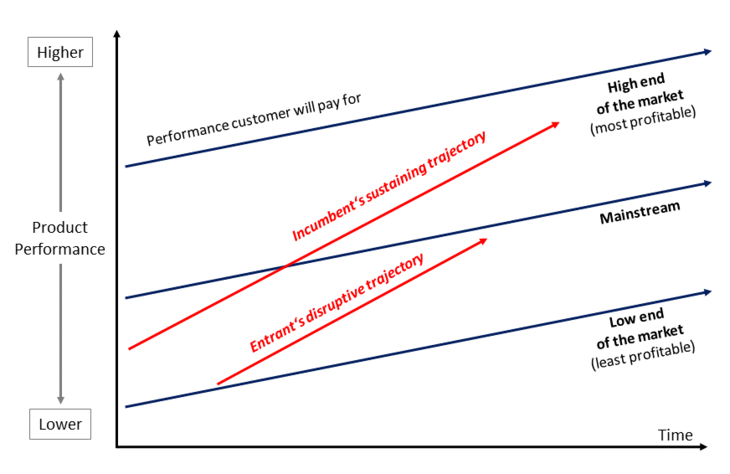

In a business context, "disruptive innovation" can be traced back to a concept put forward by Clayton M. Christensen [see Christensen/ Raynor/McDonald 2015]. According to this argument, established companies are faced with a dilemma. On the one hand, these companies are constantly attempting to develop higher performance products and services for their customers. On the other hand, this – absolutely correct – behaviour means that they leave opportunities and customers open to alternative suppliers at the lower end of the performance scale: technology overtakes market needs. Customers in this segment do not (no longer) derive any benefit from the improvements offered and turn to lower cost alternatives.

Sustaining innovation – Continuous upwards development

At the upper end of the customer segments, demanding customers are prepared to reward this progress. Accordingly, an established company with strong resources finds a very profitable and attractive customer segment, which they then focus on. Consequently, this customer group is provided with constantly higher performance solutions due to continuous innovation ("sustaining innovation") and this keeps competition at a distance. At the same time, by focusing on these customers and due to evolutionary improvements the company manoeuvres itself into a niche at the upper end of the market.

Disruptive innovation – Solutions for less demanding customers

By contrast, disruptive innovations always tend to emerge at the lower end of the performance scale. Here, you can initially find a small number of currently unattractive customers. Profit margins are correspondingly low and therefore not of interest to established or growth-oriented companies. New suppliers can take advantage of these opportunities as they present themselves by attacking established suppliers in their market by offering these less demanding customer groups innovative and, above all, alternative solutions.

These new business models based on simpler and thus lower cost alternatives are good enough for these customers to perform their actual tasks. This is how the new competitors initially succeed in gaining entry to the market. By continuously optimising their alternative solutions, they consistently come up with higher performing innovations. As a result, what they offer increasingly becomes interesting to additional customer groups and established suppliers' business models are undermined (disrupted) in the long term.

This can be briefly illustrated using the example of off-grid energy supply: In developing countries, around 2.7 billion people currently have no access to modern energy services and the associated prosperity [see BMZ]. To improve this, in Africa and Asia off-grid (i.e. independent of a major energy network) power plants and networks can effectively supply power to villages or individual houses self-sufficiently and selectively. This is always better for users than what they had before – previously there was nothing at all.

Established power generators have no response with their tried and tested solutions. The complex infrastructure for central – and doubtless efficient – production and transmission to the end user is not (or no longer) required here. Of course, energy consumption is not paid for by bank transfer but by text message from a mobile phone using "M-Pesa" [see Hughes/Susie 2007].

Fig. 02 describes this development over time.

Fig. 02: The disruptive innovation model [Source: own illustration based on Christensen/Raynor/McDonald 2015]

Alternative markets – Facilitating new consumption

In the ecosystem described above, neither power generators nor banks play a key role. Due to the disruption described, these established suppliers' business model, tailored towards economic and technological efficiency, inevitably has no impact. It is simply "over-developed" for this context.

This example shows: Innovative business models enable new companies to target different and previously fallow markets ("markets of non-consumption") – or even to invent new markets. This gives customers who previously had no (financial) opportunities at all solutions that enable them to significantly improve their own situation. These markets that have not previously been supplied are often excluded from the market monitoring carried out by established suppliers. The low level of attention and lack of competition therefore make this segment even more attractive to new entrants.

Challenge – New approaches are not possible with existing structures

Simple solutions allow a challenger easy access to the lower market segment. Continuous development of innovative and attractive solutions then leads to increasing market penetration by the challenger. The established company ultimately loses market share. It finds itself increasingly caught in a niche position, from which the company cannot free itself with its long-established corporate structure and trusted methods.

Info box 01: The test: The key questions that decision-makers have to ask themselves in this context:

- What fundamental task or (political, functional, emotional, social) challenge is the customer really faced with?

- What specific requirements does the customer have and what experiences when buying and using a product would help to provide the perfect solution?

- Do we know the real, causal reasons for purchase?

- What modules / elements relating to this customer problem do we need to combine to enable us to offer the customer the best possible solution experience?

- Can we really overcome our traditional way of working – who is the right customer for us and our long-term capabilities?

- Do we have access to the important and appropriate resources to actually implement the customer-specific innovation in the special business unit?

- Do we have appropriate processes to quickly create disruptive innovations?

- Do we have the right values, the supporting culture and the profit / growth expectations appropriate for a start-up / spin-off company?

- Do we have the right team and structure to optimally support our approach to innovation?

- Do we accept errors and an inefficient and uncertain solution process?

- Can we really deal with the associated commercial and personal uncertainty?

Possible solutions – Separating established and new

If we follow Christensen's explanation, alternative products, solutions and business models in an established environment are perceived exclusively as alien elements. Therefore, these very different approaches are rejected by existing organisations for various reasons: "It's not right for us, our capabilities, our aspirations and the way we do things here [...]". The existing organisation defends itself against the newcomer in the house. There are also some key elements that do not match: The cultures, the organisational forms, the types of interaction and the people involved are generally not compatible.

Thus, disruptive innovations never occur in an existing business context and/or with the established management. Companies that face up to the challenge of disruptive innovation and want to become disruptors themselves must therefore set up a separate new business unit (spin-off) with its own business model and specific growth and earnings expectations or acquire one of the (start-up) companies involved and continue to keep the units separate from one another.

Offer – Customers do not buy a product, they buy a solution to their problem

Disruptive innovations arise due to consistent focus on a customer problem and the task the customer has to perform. Therefore, detailed knowledge of the customer and their specific challenge (job to be done) is a key prerequisite for targeted innovation. Accordingly, it is important for the company to be familiar with the customer's task and model its business model to match. As a con- sequence, customers are segmented exclusively according to their requirements and offered specific solutions.

Contradiction – A concept is not a general theory or a forecasting method

Among those who have criticised the "disruptive innovation" concept is the Harvard historian Jill Lepore [see Lepore 2014]. She argues that the concept is based on a deep-seated fear of financial collapse and an apocalyptic fear of global destruction on the one hand. On the other hand, she criticises Christensen's arguments and the lack of empirical rigour: she claims that success criteria and case studies are arbitrarily selected to support Christensen's arguments.

The economist Joshua Gans [see Gans 2014] also contradicts the deterministic claims of Christensen's concept. The future is always uncertain and the success of disruptive innovations can ultimately only be assessed with hindsight.

Epilogue – An aggressive business model alone is not disruption

A comprehensive understanding is required to effectively utilise the disruptive innovation method (see Info box 01). Disruptive innovations begin at the lower end of existing markets or create new markets. They create an offer for customers that established suppliers ignore.

By contrast, solutions for average customers require a certain level of quality. However, this can only be achieved over time. Uber, AirBnB, Netflix and ZipCars focus their offer on exactly these "mainstream" customers. With their performance promise, they put themselves alongside the group of existing competitors. Thus, what suppliers such as Uber, AirBnB, Netflix or ZipCars offer is not disruptive innovation as defined in the theory [see Christensen/Raynor/McDonald 2015]. They are merely intermediaries who bring together supply and demand in an intelligent way.

The Silicon Valley entrepreneur and investor Peter Thiel also generally advises against disruption: Disruptors are looking for trouble – and they will get it [see Thiel/Masters 2014]. Instead of putting themselves alongside the established companies, start-ups should create something better and genuinely new. New thinking and solving fundamental problems have always been the basis for progress, jobs and prosperity.

For established suppliers, there are two fundamental risks: Firstly, there is the danger that alternative suppliers and the simple solutions they offer will not actually be perceived because market monitoring is restricted to familiar markets and competitors (perception risk). Later, these alternatives are dismissed as low grade and insignificant, based on their current profitability, in an effort to confirm the company's own leading position (arrogance risk). This will inevitably lead to the dilemma described here. There is no doubt that this applies to economics – but of course it is also the case in politics with the solutions offered there.

Therefore, established suppliers have to look in every direction for relevant information and pay attention to early warning indicators. Under no circumstances – as they do all too frequently – should they rest on their laurels. They have to take these potential new competitors seriously. However, not everything is disruptive even if the tech disciples in Silicon Valley are convinced it is. Innovative trends can certainly be identified in some areas, but they are not nearly as new as they are generally claimed to be. Many years ago, the newly set up online banks that are now established definitely had disruptive potential, but it was the established market agents who put it to the best use. The following lessons can be learned from this: It is essential to systematically develop the existing business model and to effectively apply the relevant risk management methods in all areas.

Many market agents all too often forget that companies generally get into difficulty as a result of poor strategic decisions. It is strategic risks that blow companies out of the market, not operational issues. Therefore, companies should bid farewell to "risk accounting" that has a purely operational focus and is based on looking back. Entrepreneurs of all kinds should concentrate their activities on commercial opportunities and the associated uncertainty and existence-threatening (future) risks. It is essential for companies to get to grips with potential future scenarios, so that they can learn from the future and actively shape it.

Literature

- Bundesministerium für wirtschaftliche Zusammenarbeit und Entwicklung [German Ministry for Economic Cooperation and Development] (BMZ) [2016]: Zukunftscharta EINEWELT – Unsere Verantwortung; Internationale Energiepartnerschaften des Bundesministeriums für wirtschaftliche Zusammenarbeit und Entwicklung [ ONE WORLD future charter – Our responsibility; The Ministry of Economic Cooperation and Development's international energy partnerships]; www.bmz.de/de/themen/energie/partnerschaften/ [downloaded on 06 December 2016].

- Christensen, Clayton M./Overdorf Michael [2000]: Meeting the Challenge of Disruptive Change, in: Harvard Business Review, Mar.-Apr. 2000, p. 66-76.

- Christensen/Clayton R./Raynor, Michael/McDonald, Rory [2015]: What is disruptive innovation?, in: Harvard Business Review; Dec. 2015; p. 49.

- EY [2016]: The upside of disruption, Megatrends shaping 2016 and beyond, 2016. Gans, Joshua [2014]: The easy target that is the Theory of Disruptive Innovation, Link: www.digitopoly.org/2014/06/16/the-easy-target-that-is-the-theory-of-disruptive-innovation/

- Hughes, Nick/ Susie, Lonie [2007]: "M-PESA: mobile money for the "unbanked” turning cellphones into 24-hour tellers in Kenya." In: Innovations: Technology, Governance, Globalization; Winter / Spring 2007, Vol. 2, No. 1-2, pp. 63-81

- Lepore, Jill [2014]: The Disruption Machine: What the gospel of innovation gets wrong, in: The New Yorker, 23 June 2014.

Lobo, Sascha [2014]: Auf dem Weg in die Dumpinghölle [On the Way to Dumping Hell], Source: Spiegel Online, 03 September 2014, link: www.spiegel.de/netzwelt/netzpo- litik/sascha-lobo-sharing-economy-wie-bei-uber-ist-plattform-kapitalismus-a-989584.html - Meck, Georg/Weiguny, Bettina [2015]: Disruption, Baby, Disruption!, in FAZ, 27 December 2015.

- Ramge, Thomas [2015]: Die drei Zauberworte [The Three Magic Words], in: brand eins, Issue 04/2015.

- Romeike, Frank [2016]: Disruptive Innovation [Disprutive Innovation], in: Der Aufsichtsrat, 10/2016, p. 147.

- Schumpeter, Joseph A. [2005]: Kapitalismus, Sozialismus und Demokratie [Capitalism, Socialism and Democracy]; 8th edition; UTB; Stuttgart.

- Thiel, Peter/Masters, Blake [2014]: Zero to One – Zero to One: Notes on Startups, or How to Build the Future, Crown Business, New York, p. 56

Authors

Andreas Kempf, Dr. oec. HSG, Senior Vice President Internal Audit, Risk and Quality Management, ZEISS Group and researcher on effective corporate governance

Frank Romeike, Managing Director of RiskNET GmbH and board member of the Association for Risk Management and Regulation